July 7, 2014, 3:53 PM ET - Wall Street Journal

Fewer People Are Quitting Their Jobs, And Why Thatfs Not Good

By Kathleen Madigan

Payroll growth finally has taken off this year, rising solidly above 200,000

jobs per month in the first six months.

But what lies beneath the headline number says a lot about the economic

outlook. Economists at Goldman

Sachs set out to gauge how dynamic the current

labor markets are. What they found is therefs much less job movement than there

would be in a fully healthy economy. Businesses adding and losing workers and

people quitting and taking other jobs–what economists call gchurnh—are generally

good measures of economic confidence.

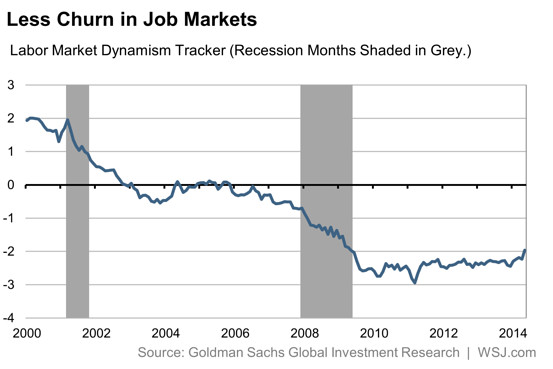

Goldman constructed a labor-market dynamism tracker using data from a range

of government sources. They took the hiring and separation rates in the Job Openings and Labor

Turnover survey, the sum of the gross job-gain and job-loss rates from the Business Employment

Dynamics report, and the share of workers making job-to-job transitions in

the employment

reportes household survey. (The tracker prior to the mid-1990s relies on

annual household survey data.)

The tracker finds labor-market dynamism ghas fallen substantially since

2000.h Dynamism rebounded only weakly in the last two recessions, compared to

much stronger bouncebacks following the recessions in the 1980s and 1990s.

Companies are laying off far fewer workers, but the hiring rate has recovered

only partly from the recession. People are quitting less often, and workers show

a greater tendency to stay put. Although some of the reduced churn reflects

structural effects, gthe decline seems mostly cyclical in nature,h writes

David Mericle, a U.S. economist at Goldman.

Does a less dynamic labor market matter if top-line job growth is doing well?

Yes, the report says.

First, a more static labor market gis likely to see weaker wage and

productivity growth.h

Workers may stay put in jobs that donft use their skills to the best effect.

That mismatch reduces an employeefs ability to negotiate pay raises and also

reduces his or her productivity. In addition, the Goldman report notes other

research showing a large share of an individualfs wage gains comes from

switching employers.

Second, less churn exacerbates the challenges faced by the long-term

unemployed.

gA labor market with little turnover is naturally more difficult to enter for

those not currently employed,h Mr. Mericle writes.

According to Labor Department data, in this recovery, the longer a person is

out of work, the lower the chances of finding a new job. In addition to the

personal and government costs of long-term unemployment, a large number of

permanently unemployed workers reduces the U.S. economyfs potential output.

Add that drag to weaker wage and productivity growth, and itfs easy to see

why the Federal Reserve is concerned about labor-market churn.

gWe suspect that such concerns lie behind Chair[woman Janet]

Yellenes inclusion of the hiring and quits rate in her edashboardf of

labor market indicators,h Mr. Mericle concludes.

Indeed, Ms. Yellenfs dashboard is why Tuesdayfs Job Openings and Labor

Turnover report, once an also-ran among economic data, has become a must-read

release among Fed watchers.